This is a guest post by Joshua Meah. Meah is a former research intern with the New America Foundation’s “American Strategy Program.” He is writing from Mumbai, India.

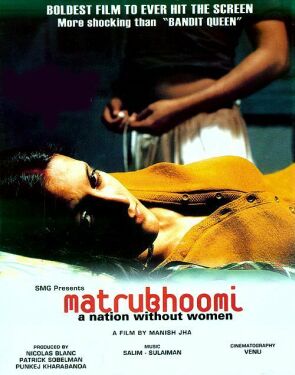

Matrubhoomi: A Nation Without Women, an Indian film by Manish Jha, is one of the most intense, thought-provoking, heart-wrenching and brutally honest cinematic experiences of my lifetime. Imagine the American science-fiction hit “Children of Men,” but set in a small village in rural India. Then, imagine that the problem isn’t that no one is capable of pregnancy; rather, there are no women. Of any age, no girls or women have been seen in a village for fifteen years. They’ve all, minus one young girl discovered later in the movie, been killed off.

This is the premise of the movie. The film goes on to skillfully raise questions of great importance related to gender, caste, class, violence, and the Indian family.

Such a scenario is the logical end-point of even some current village practices, which lends the film its stark brilliance and credibility. At the film’s conclusion, it is noted that, according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and UNFPA, over the past century thirty-five million women have disappeared due to acts related to gender discrimination. Many of the disappearances are linked to the dowry practice, which requires the family of the bride to pay a substantial contribution (money, cows, etc.) to the family of the groom. In a village where the average income is half of the United Nation’s marker used to indicate “poverty,” such a practice is often unfeasible. Parents, in anticipation of an impending dowry payment, would kill female infants immediately after birth.

Domestic violence also claims a substantial number of victims and lives. On the rooftop of a small NGO-funded school in Veranasi, India, the Hindu religious capital of the world and home to the River Ganges, I sat with a group of twenty students, ages eight through sixteen, from the surrounding basti (slum). I asked them (this conversation as in Hindi), “What are the greatest problems faced by Veranasi today?” The children’s unified response on one issue was unnerving and illuminating, shining light on what is possibly India’s most sensitive topic aside from caste. Family.

They said “Each night, the men go out and drink. Then they come home and beat their children and wives. The wives, in fear and often in the real belief that they themselves have done something horrible to deserve their treatment, will then light themselves on fire. Some will die.”

As I learned from further study and interviews, the alcohol consumed is not actually alcohol. It’s a petroleum-based substance laced with other narcotics that pass through the heart of the city. A good “high” costs no more than 10 cents USD. Like crack in the inner-cities of America, this drug rips through Veranasi’s slums, shattering families in the process. The drug is too cheap, the rage byproduct too strong, and the use of violence against women is just too easy. In other locations of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, I’ve found similar stories of violence, though not all are necessarily linked to drugs.

India n. (perhaps it has potential as an adjective as well?): the land where the opposite of everything is always at least a little bit true. This is the same country that has produced a great number of enormously powerful female politicians long before America even honestly broached the subject – Indira Gandhi being the case in point. Even now, the head of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state and the home to 130 million people, is headed by a woman of dalit origin (India’s lowest caste). The progress of India’s democracy in terms of its movement toward social equality has in some ways been as breathtaking as it is heartbreaking.

With Indian elections, perhaps truly the greatest “show on earth,” coming up in less than a month and a half, election observers would do well to hold a movie like Matrubhoomi close to their hearts. One goal of India’s democracy, as is written by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus on the general subject of poverty, should be to relegate the sharp kernel of truth within this movie to nowhere else in human civilization except museums.

— Joshua Meah

5 comments on “The Sad Truth in a Story about an India without Women”