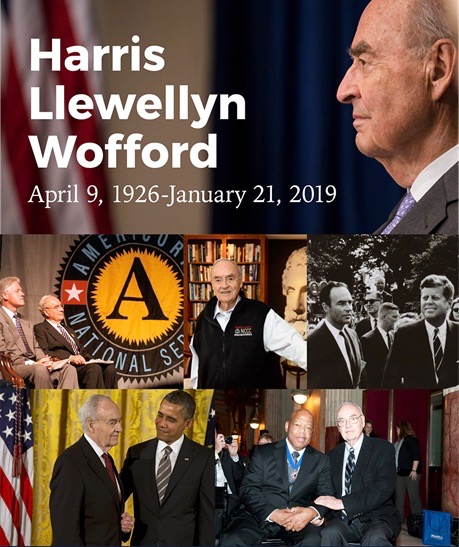

Only a funeral, it seems, truly brings Washington together these days. Yesterday nearly a thousand guests, including distinguished emissaries from the Bush, Clinton, and Obama worlds, gathered at Howard University to honor Harris Wofford.

Only a funeral, it seems, truly brings Washington together these days. Yesterday nearly a thousand guests, including distinguished emissaries from the Bush, Clinton, and Obama worlds, gathered at Howard University to honor Harris Wofford.

That cross-party appeal sadly feels like the artifact of a bygone era, but Wofford—ex-senator, godfather of the American service movement, and man who “saved Martin [Luther King’s] life with a phone call”—shouldn’t be relegated to some stuffy realm of bipartisan dreamers. Such a portrayal makes it easy to dismiss his example as impractical for today’s world. But he was no idealist; in fact, his story offers a solution to our ongoing political strife. He knew firsthand that every American can change our country the same way he did: by taking personal responsibility for solving the problems you see around you.

Senator Wofford embodied that approach himself. Fittingly, yesterday’s memorial took place at Howard, where he was the first white male graduate of the law school in 1954—a personal commitment to desegregation that Rep. John Lewis judged nearly “unreal, unbelievable” given the stigmas of the era. Wofford soon befriended a young preacher, Martin Luther King, Jr. Appropriately, this weekend is also the fifty-fourth anniversary of Bloody Sunday, after which Wofford was the only government official who rallied to King’s call and marched with him at Selma.

When I first approached Senator Wofford a decade ago, a nervous 18-year-old seeking to make a documentary on his life, he laughed and agreed to do one interview on the subject. A living history book, he had sipped tea with Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House, lunched with Albert Einstein in his Princeton home, and dined with Nikita Khrushchev at the Kremlin. In the midst of trying to order my own nascent life, I was eager to learn lessons from his. My enthusiasm led to extensive travels, filming him around the country, and after several years he began to jokingly refer to me as his “poor Boswell.”

Into his late eighties, Harris would drive us as I filmed in his battered green Ford Taurus, affixed with a cornucopia of overlapping political bumper stickers—about thirty for then-Senator Barack Obama—more suggestive of a lunatic than an ex-senator. He would quote poetry and discuss his passions, especially the importance of Mahatma Gandhi. Harris and his late wife, Clare, possessed a dazzling command of Gandhian lore after spending a year on the Mahatma’s trail in India. In particular, he enjoyed telling the story of Gandhi’s reaction upon arriving at a 1901 gathering of leaders of the Indian independence (Swaraj) movement to find an unbearable stink rising from untended latrines. Told only untouchables could clean the latrines and none were available, Gandhi asked for a broom. The crowd watched in shock as he set to work cleaning the filthy latrines himself. His message: “Why wait till the advent of Swaraj for the necessary drain-cleaning?”

That self-actuating lesson—doing something concrete right now, no matter who you are, to improve the lives of those around you—struck a deep chord. Direct action became the Wofford trademark. Weeks before the 1960 Election, Dr. King was arrested in Georgia and thrown into a dangerous prison. Harris was serving as civil rights advisor to John Kennedy and his immediate instinct was that a personal signal of concern from the presidential candidate would be the most effective help for his friend. He was proven right. The empathetic gesture of Kennedy calling with sympathy led to King’s release and touched the hearts of African American voters (including King’s own GOP-leaning father, who pledged to swing 50,000 votes), providing JFK’s narrow margin of victory. It was King’s close aide, Andy Young, who confided to me: “For us, Harris was always the one who maybe saved Martin’s life with a phone call.”

Such behind-the-scenes action goes against our conventional view of history. We often focus on the figureheads—the Kennedys and Dr. King striving for civil rights, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama pushing for health care—yet Harris, not seeking attention for himself, took concrete steps that opened the door to those major changes. Reckoning with his own white privilege in the late 1940s, long before that term entered common usage, he enrolled at Howard and threw himself wholeheartedly into the civil rights movement at Selma and beyond—his dedication was so apparent that an alarmed Robert Kennedy once confided in a friend that Harris could be “a slight madman” in his zeal for equality.

A sole moment in the spotlight came at age 65 when he was elected to the Senate—like Scott Brown and Doug Jones, his was an unexpected victory that stunned Washington. He used that platform to create a domestic Peace Corps, AmeriCorps (funder of City Year and Teach for America), and fought to keep it a bipartisan priority.

His Senate tenure was brief, and he often reminded me to include not just his upset victory but also his subsequent defeat. Following his lead, I arranged a joint documentary interview with Rick Santorum, the acerbic arch-conservative who had beaten him. To my surprise, these political polar opposites drew up chairs next to each other. Santorum told me how Harris had sought him out—cornering him on a Capitol Hill balcony—and proceeded to change his mind about AmeriCorps. “We disagree about 95% of issues” Harris said, “but we’re ready to take action together on the 5%.” He knew serving something larger than yourself leads to a shared sense of responsibility, an antidote to the partisanship tearing at America’s soul.

Since 2016, he acknowledged this work was unfinished, and in fact losing ground. Harris would visit the Lincoln Memorial late at night to restore his spirits, reading aloud the Gettysburg Address. One recent evening I went with him to record this ritual. Standing together, staring at Lincoln’s statue, he confided his hope that young people like myself would learn to stop delegating responsibility for fixing our shared problems to elected leaders, too often succumbing to apathy when they fail, and instead become part of the solution. He called this “cracking the atom of civic power,” inculcating “active duty citizens” who feel empowered to ask for a broom themselves.

Not long ago, I drove along with Harris for a visit to his childhood home in East Tennessee. Standing on a wooded bluff overlooking the cemetery where generations of Woffords have been buried, I felt the scene was perfect for him to say something suitably profound to conclude the film. Instead, he was quiet. Later, as we sat at a Waffle House, he told me he had been pondering the only words of Gandhi he never felt prepared to adopt: “My life is my message.”

Such all-consuming fervor felt inhuman, he said. Returning to those words this weekend, I want to tell him they really do apply. His uniqueness stems from the fact that he was not an ideologue, but instead a man who accomplished remarkable things while remaining grounded in reality.

I made change happen, Harris was telling us, and you can do the same.

— Jacob Finkel

This is a guest post for The Washington Note by Jacob Finkel, a filmmaker and law student at Stanford University. He directed the documentary film Slightly Mad, and this segment of the film on civil rights was shown at the memorial service:

Slightly Mad: Civil Rights Excerpt from CCD on Vimeo.

One comment on “Ode to Harris Wofford: Slight Madman in Zeal for Equality”