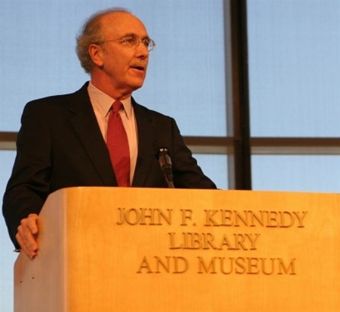

I just learned that John Shattuck, President and CEO of the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, will be shifting from his current duties to assume the helm as president and rector of the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary.

I just learned that John Shattuck, President and CEO of the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, will be shifting from his current duties to assume the helm as president and rector of the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary.

I find this interesting and important news because this university, established in large part through the support of George Soros, has been a powerhouse in training many people to become the clerks, and policy analysts, and political organizers and agitators, and bureaucrats of open societies in much of Eastern Europe. Soros and his philanthropic work and allies have played a vital role in the transformational development of illiberal regimes into more liberal ones. And where impunity and strongly consolidated, anti-democratic power preserved its interests in the former USSR, Soros’ CEU trained graduates are the most likely political rivals to abusive, undemocratic power.

Ever since George W. Bush launched a crusade to democratize much of the Middle East and other parts of the world by force, sometimes with sanctions and sometimes guns, I have struggled with the question of how to get “transformational diplomacy” right.

Condoleezza Rice in a January 2006 speech at Georgetown University admitted that America needed to “enhance [its] ability to work more effectively at the critical intersections of diplomacy, democracy promotion, economic reconstruction, and military security.”

Rice also said, concluding her remarks, that “America has come a long way and America stands as a symbol but also a reality for all of those who have a long way to go, that democracy is hard and democracy takes time, but democracy is always worth it.”

I think Soros and Rice would agree on her conclusion — but as to what democracy looks like and how to inspire and animate the spread of democracy and healthy, liberal civil society — there would be much dispute. My own feeling is that Soros has always understood “transformational diplomacy” and how to engineer a political ecosystem in which democratic process might take root more than most democracy promoters in the US government.

But now John Shattuck, former Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor in the Clinton administration, will be taking the helm of this educational institution — which has been a primary driver of the talent needed to transform political systems.

I had some contact with Shattuck in the 1990s when I worked in the US Senate on foreign policy — and was intrigued with his decision to leave the Kennedy Library Foundation and move to Hungary to run a university — and so called him.

Shattuck, who also teaches international relations at Tufts and who has been a Vice President at Harvard, asserted that we are at an exciting pivot point in the development of many transitional societies and have an opportunity to reintroduce what democracy really means — not just ballotocracy — but rather established rights of minorities, functioning courts, support of civil liberties and freedom of expression, and self determination. Shattuck thinks that the stress of a global financial crisis and the chastening of the old frameworks of power have presented a new opportunity to promote rule of law, genuine democracy, and economic progress in the developing world.

The Central European University has students from more than 100 countries and is a European/American hybrid institution that attempts to inculcate students with the tools used to achieve an open society — and to systematically prepare future change agents to understand what the real building blocks of democratic transition are. There are students not just from Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Caucasus, but also North Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

Parliament members, Justice Ministers, United Nations representatives, and countless number of civil society leaders in Eastern Europe were trained at CEU and have made a difference in their countries in ways far more rooted in their respective countries, and organically grounded, than the militarized model in nation building and democracy development that George W. Bush’s administration pushed.

John Shattuck told me that he planned to create an “international school of public policy” that would connect in an interdisciplinary way the work that CEU already has going in environmental studies, rule of law, and democracy — in order to generate more policy and political practitioners who could synthesize these different issues.

I asked him how he could make the “global justice” field less fuzzy, less idealistic, less utopian, and more results driven and results-rewarded or punished than it seemed to me to be.

Shattuck said that we needed a more sophisticated understanding of democratic development and of open society and needed to generate process templates that might work for those trying to challenge illiberal political regimes. But he said that there is “no blueprint” for open society. Every case is “country and society specific.”

Shattuck said that the means by which a democratic system or state emerges will be different in each case — but that there are many lessons that can be learned in these cases by organically rooted political actors, activists, bureaucrats, academics, the media, and so on. But what is clear, Shattuck said, is that “democratic values cannot be imposed from above.”

I think the world needs talent production shops like the one at CEU that Shattuck will take over next year (his start date is August 1, 2009) and not depend only on the exclusive elite clubs on the world’s upper crust Ivy League institutions.

We need many more people around the world who can think in disciplined and realistic ways about social and political change and who can implement an open society strategy from a position of strength and competence.

This is the only thing that will help show that the kind of force driven democracy promotion we have seen during the Bush administration is weak, ineffective, and undermines the not only democracy promotion abroad but our own democratic institutions at home.

Given Caroline Kennedy’s friendship with Barack Obama and her association with Shattuck at a presidential library built around her father’s ideas, Kennedy is in a good position to help Obama understand the difference between the falsehood of democracy pursued through force and democratic practice built on training a generation of people who can actually operate and help to instigate genuine democratic transition.

This is part of what we need to make “democracy” a good word again.

— Steve Clemons

14 comments on “Teaching Transformational Diplomacy and Making “Democracy” a Good Word Again”