The New Yorker‘s Laura Secor has a richly detailed account of some complicated history that runs between Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Ali Khamenei. The whole piece should be read, but here’s a key clip:

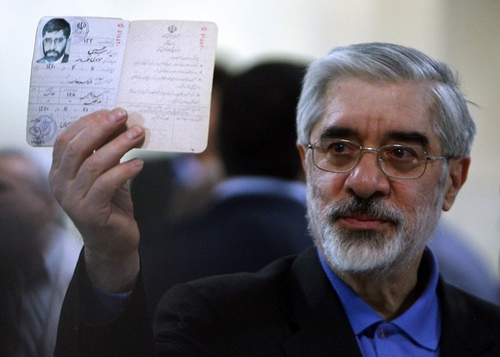

Mir-Hossein Moussavi, the Presidential contender whose legions of supporters have taken to the streets of Iranian cities, has a long and complex history with Khamenei. When Moussavi was Prime Minister, in the nineteen-eighties, he belonged to a faction known as the Islamic Left. It shared power with a rival faction, the Islamic Right, led by Khamenei, who was then the President. When Moussavi and Khamenei clashed, as they often did, the charismatic leader of the Islamic Revolution and the supreme leader of the country, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, intervened–most frequently on Moussavi’s side.

So, in 1989, when Khomeini died and Khamenei replaced him as supreme leader, the Islamic Left was exiled to political purgatory. Moussavi did not lift his head in Iranian politics for twenty years. But during those years the rest of his Islamic Left faction, including Saeed Hajjarian, made one of the most dramatic turnabouts in Iran’s political history. It abandoned its hard-line commitments in favor of an agenda of liberalization, freedom of expression, the relaxation of Islamic social codes, and friendlier dealings with the world. On the strength of this platform, in 1997, Khatami, who had been Moussavi’s minister of culture, won the Presidency in a landslide. Parliament soon fell to the reformists, too. Although these elected officials were subordinate to Khamenei, Hajjarian believed that they could extend their reach by triangulating between the mass movement they represented and the autocratic state with which they shared power. He coined the phrase that would define the reformists’ strategy: “Pressure from below, negotiation at the top.”

That strategy failed. The pressure from below was for far-reaching democratic reform, which Khatami could not deliver within the confines of the constitution. Moreover, the authorities at the top were not interested in negotiating. A hundred independent newspapers and magazines opened, only to be forced to close; the Guardian Council vetoed much of the legislation passed by the parliament; and Khatami could not keep his inner circle out of prison, let alone the young people whose votes had won him the Presidency. By the time he left office, in 2005, the reformists had neither a credible leader nor a constituency. Activists and public figures called for a boycott of that year’s election. What good was voting if a President with a broad popular mandate could still be controlled and stymied by unelected powers? What difference did it even make who was President?

A major one, as it turned out. Under Ahmadinejad, a crackdown on dissent forced scores of journalists, intellectuals, and activists to flee the country. Ahmadinejad centralized government, empowered the Basij militia and the Revolutionary Guards, flouted expert economic advice, and packed the ministries with ideological cronies. With few reformists permitted to run in the interim elections of 2006 and 2008, liberals and moderates had little recourse inside the political system. Iran seemed headed for a confrontation between irreconcilables: the forces for secular democracy and those for autocratic theocracy.

— Steve Clemons

4 comments on “Laura Secor on Iran’s Protest Vote”