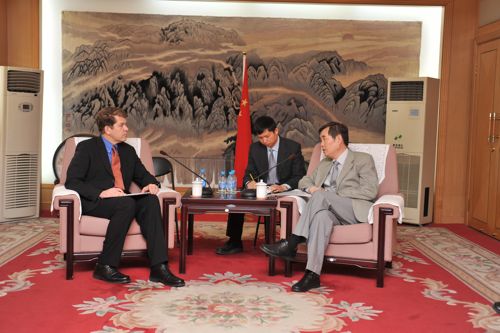

(Washington Note publisher Steve Clemons with State Council Information Office Vice Minister Qian Xiaoquian)

As of the end of 2008, China claimed 298 million “netizens” — or regular users of the internet.

At that same benchmark in time, China had 162 million blog sites and 117 million mobile internet users.

By the end of June 2009, Chinese authorities predict a 20% growth jump in all these figures.

Like all American journalists or public policy hands who visit China, I have been interested in what sites one could not get on to. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are the perennial blocked sites (though Chinese authorities permitted access to most these sites during the Olympic Games). However, to be quite honest, many of the sites — particularly news and information sites that I could not access a year ago when i was in Beijing — are available.

I have been checking news and policy websites in the UK, France, Germany, Iran, Russia, Canada, Poland, Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, and others to see significant blocks — but the only newspaper I have not been able to get that I wanted to get was the Philadelphia Inquirer — which a young person here showed me how to reach through a back channel site.

In fact, this young person walking through internet access issues with me said that Chinese young people can essentially access anything that the government might try and does block. This person who works in international affairs says that the ability of the Chinese government to significantly control access to web-based content is quickly eroding.

And as a result of very interesting and candid discussions with the Vice Minister of the State Council Information Office, Qian Xiaoqian, I believe that many Chinese government officials know that the practice of blocking this site or that is undergoing significant change or reform. According to Vice Minister Qian, Chinese authorities restrict access to sites based on four principal criteria: the incitement of hatred between ethnic groups, racial discrimination, pornography, and violence. He said that since China’s reform process started 30 years ago, the State and China’s citizens have moved into a mode of significant tolerance of criticism and dissent but that the government still objected and would intervene to “oppose fabrication of stories.”

I’m sure that many will continue to argue for some time that the Chinese government plays an oppressive force when it comes to internet management and monitoring.

But I disagree.

There is simply just too much internet use. Terminals are everywhere. The newspapers are actually full of stories about people critiquing government officials, standards, building and infrastructure quality. It’s fascinating — not perfect. I do get the sense that political entrepreneurship is mostly a non-starter here, but even on that front, I have found several key cases where even that form of self-censorship is changing for the better.

As the State Council Information Office official told me, all of this could not be happening if the Chinese government didn’t view the expansion and deployment of the internet “positively.”

In my exchange with the Vice Minister, I mentioned that Senate Foreign Relations Committee Ranking Member Richard Lugar‘s office had sent me an email that morning about an exchange that Senator Lugar had had with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

The email from Lugar was not “text” but rather a hyperlink to Richard Lugar’s YouTube site, which archives a lot of video recorded exchanges between Senator Lugar with the world’s leading foreign policy personalities.

I conveyed to Vice Minister Qian that YouTube was not available and was one of the blocked sites — most likely because of concerns over “fabrication” of things which the Chinese government deems to be untrue or of serious national security consequence.

Vice Minister Qian was not defensive — and made no claims that he would get YouTube unblocked (he didn’t realize it was blocked) but said that by my description of the site and of Lugar’s use of the YouTube medium, it may be something that Qian should look into using for his office’s own work in public diplomacy. Pretty surprising and refreshing answer.

Some may see the practice of filtering sites to be disturbing and to be ‘the story’ that needs to be told.

But I have to say that even with my skeptic’s eye, the trends in China are very positive when it comes to public inquiry over the net and when it comes to the forward-leaning, more enlightened stance of many government officials who are incrementally liberalizing access. That I think is the real story.

It will be interesting to see if access to YouTube is restored before my next visit to China.

In Wuxi today seeing a solar panel maker and to Shenzhen tomorrow.

— Steve Clemons

14 comments on “China’s Surging Netizen Culture and Government’s Response”