Today, I was reading through some of the Witness episodes and write-ups produced by Al Jazeera and ran across Silent War: How Rape Became a Weapon in Syria. One of the brave women willing to share said:

Today, I was reading through some of the Witness episodes and write-ups produced by Al Jazeera and ran across Silent War: How Rape Became a Weapon in Syria. One of the brave women willing to share said:

They started to rape women at roadblocks, at home in front of their husbands, their children …. At some point, the regime took a new approach. It recorded videos of the rapes of women in detention and sent them to the fighters.

And as we have seen in recent accusations surrounding the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation hearings and more recently alleged against Virginia Lieutenant Governor Justin Fairfax, or the struggles with widespread violent sexual assault inside the US military, the mistreatment of and subjugation of women is a crime far too familiar at home.

#MeToo is helping to raise awareness and strengthen the foundation beneath victims. There are global initiatives like one supported by French Minister for Gender Equality Marlène Schiappa that would establish a Council for Gender Equality in the G7. Not sure whether this will help or hurt the cause, but French President Emmanuel Macron is trying to entice Ivanka Trump to join it. I get stuff like this. A global infrastructure of polite meetings and councils that actually puts the abuse of women on national agendas is important, but the urgency and scale of this gross side of society are being neglected.

Both at home in America and in countries abroad, I feel that there have been such systemic, industrial scale assaults on women, particularly in wars and conflicts, that we need much more comprehensive discussion. There are atrocities occurring today in conflict zones, in refugee camps – and there are abuses in calm parts of the world where talking about rape and the degradation of women have become taboo, hidden matters feeding a quiet dysfunction that just perpetuates the harm, not healing it.

Again, this brutality against women and girls isn’t remote from us. As the Washington Post‘s Christian Caryl emphasizes in his passionate plea for awareness of conflict rape, he punctuates that this is all happening “Right Now. Today.”

I’ve only written occasionally about this important subject, and not in the depth it deserved. I’ve had just a few personal brushes with people where the trauma of weaponized rape and violence towards women left me dazed and uncertain how to respond. The truth is I haven’t really known how to surface a subject so important, but yet, remote from my own daily life. But lately, I have come to understand that that remoteness is an illusion. This problem is real and close, if not overtly, it lurks in our society psychologically and emotionally.

I want to share some of these episodes where I’ve learned about brutality against women.

America has its own conflict zones in the home, a ‘war on women’ in other form. Read the cases of the DC Volunteer Lawyers Program that are overwhelmingly about victims of domestic violence. Kathleen Biden, former daughter-in-law of Vice President Joe Biden, is a hero in my world for connecting me to the lawyers who offer pro bono support to victims of abuse and rape. Cheryl Masri, another friend, has tearfully recounted stories of friends of hers savagely beaten and inhumanely controlled by partners. She co-founded Knock Out Abuse to support them.

This violence is happening internationally, and we shouldn’t be shrugging off the revelations. The weaponization of rape is commonplace in conflicts — and we have a lot of conflict zones around the world today. Hundreds of young girls were kidnapped by Boko Haram in Nigeria for forced marriage and rape and received a spike of news interest and then largely disappeared from the dashboard of global concern. Today, Rohingyan Muslims are victimized, raped, harassed and murdered by Myanmar military forces — and the attention given in our aggregated global media is scant and the pressure on the government there to change course just not enough to matter.

These experiences need to be acknowledged at a much higher level than they are today. These crimes need to be surfaced and the stigma lifted from victims. There won’t be healing if the stories and experiences are just shoved into darkness and places identified as taboo. So with this note, I’m hoping to focus some attention on one of humanity’s miserable corners.

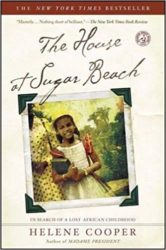

My own understanding of rape’s place in conflicts went from sterile distance to nightmarish closeness after reading Helene Cooper’s The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood. I knew that Helen Cooper, a New York Times correspondent who has covered American diplomatic and national security affairs as well as Obama’s White House, could tell a story, but I was unprepared for the revelations in her book.

My own understanding of rape’s place in conflicts went from sterile distance to nightmarish closeness after reading Helene Cooper’s The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood. I knew that Helen Cooper, a New York Times correspondent who has covered American diplomatic and national security affairs as well as Obama’s White House, could tell a story, but I was unprepared for the revelations in her book.

As she recounted a blissful, privileged, upper middle class life in Liberia torn to the ground during the 1980 military coup which included her dad getting shot and the execution of her cousin who was Liberia’s foreign minister, Cooper told the story of her mom preempting the rape of her three children, including Helene, by offering her body as the object of brutal gang rape to a group of young Liberian military hooligans. Helene and her sisters Marlene and Eunice knew it was happening, and their mother had saved them.

This was the first time that the notion of ‘conflict or war rape’ had become real for me — and as I sat in the presence of Calista Cooper, Helene’s and Marlene’s and Eunice’s mom, I got the shakes. My teeth were chattering. I was nervous, and I tried to overcome it with flamboyant boisterousness at a dinner party hosted by Helene. The elder Cooper matriarch who had endured the unendurable calmly told me, smiling, “settle down sea crab.” I don’t think I ever told Helene how much her book had ruined my distant appreciation of the horrors of conflict and had taken me so close into it, and into a storm.

A couple of years later, I watched Angelina Jolie’s In the Land of Blood and Honey that takes one into a journey of the human perversions and female degradation of the Bosnian War. I saw the film and sat just behind Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg. I talked to Jolie and her then-husband Brad Pitt after. Pitt told me that the film was of extraordinary personal importance to his wife — and shared the tidbit that he had violated union rules by appearing as a stunt man in one of the war scenes.

A couple of years later, I watched Angelina Jolie’s In the Land of Blood and Honey that takes one into a journey of the human perversions and female degradation of the Bosnian War. I saw the film and sat just behind Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg. I talked to Jolie and her then-husband Brad Pitt after. Pitt told me that the film was of extraordinary personal importance to his wife — and shared the tidbit that he had violated union rules by appearing as a stunt man in one of the war scenes.

Name-dropping aside, what changed for me that night was listening to many women that evening in separate huddles around Ginsberg and Jolie confessing their own past victimhood. I say ‘confessing’ because in the stories, one could feel that they felt guilt for being raped, terrorized, manhandled, and for being quiet about it. They felt guilty that their friends, brothers and sisters, or parents, and relatives had been maimed and murdered. I listened to stories from them that night in which family members had been raped, tortured and in some cases murdered by agents of state governments. Angelina Jolie never cut any one off and asked each person clustered around her to finish her story. Tears flowed down their cheeks. We were in the Holocaust Museum. The same true around Justice Ginsberg. She listened, and she reached out and held the hands and wrists of women telling their dark secrets in the chaotic moments in a lobby after that movie’s end.

I couldn’t sleep that night. I got a screener of the film and watched it again. I just felt such confused nausea knowing that vast numbers of women had been murdered and raped in conflicts as part of a subjugation and domination “plan.” I had always known of and supported the erasure of historical amnesia about Japan’s “comfort women” in Korea and China before and during World War II — but I had not ever stepped over that line of intellectual distance to emotional inclusion in the horror of it all.

Recently this turbulence was stirred in me again when I watched a clip of journalist Nina Easton, who now produces documentary style stories on notable leaders, interviewing former Kosovo President Atifete Jahjaga at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The topic was rape as a weapon of war during the Kosovo War.

Tracking with Helene Cooper’s book and the Liberian Civil War, Jahjaga recounts meeting women who were victimized in the Kosovo War and who were raped alongside their daughters and mothers and neighbors. One mother and all of her children were brutally gang raped. Her daughters, according to Jahjaga, were 17, 15, and 13.

Tracking with Helene Cooper’s book and the Liberian Civil War, Jahjaga recounts meeting women who were victimized in the Kosovo War and who were raped alongside their daughters and mothers and neighbors. One mother and all of her children were brutally gang raped. Her daughters, according to Jahjaga, were 17, 15, and 13.

Another woman was regularly raped in the shed behind a factory over a period of six months, often in front of her children. And when the military had to pull back, on the final day they raped her five year old daughter.

I asked the CSIS Smart Power, Smart Women Initiative for both the long clip of the entire discussion with Easton — and also this one of brutal intensity that lasts 17 minutes long. It should be watched. Or read.

The former Kosovo President strikes out at the United Nations for perpetuating the sickness of these crimes by not including them in UN reports on violence against women on the grounds that Kosovo is not yet recognized in the body as a sovereign nation. The former President says more than 20,000 women who have suffered from rape, torture, and murder are forgotten victims.

She says that after conflicts, societies want to forget these crimes, and the subject becomes taboo — the victims stigmatized.

She recounts how women’s “bodies were turned into a battlefield – and their rapes became a weapon of war.”

Perhaps the first part of doing something about the pervasiveness of abuse in our homes and in conflict zones is to know of these kinds of stories, and to know that they are happening to people we know. And in that spirit, I share these troubling vignettes and encounters and agree with former President Jahjaga that these cycles will continue until the stigma that hangs over the victims is ended, and that we talk about the habits of abuse in our social equation.

— Steve Clemons

2 comments on “Women, Abuse, and Weaponized Rape”