This post also appears at The American Strategist.

This post also appears at The American Strategist.

This year’s Failed States Index from Foreign Policy magazine is interesting not only for the questions the Index raises about failing states, but also for the questions it poses about the very act of measuring state stability (you can read about FP’s methodology here).

One article released as part of the Index, written by Robert Rotberg of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, raises questions about the Index itself. Rotberg discusses some of the “puzzling” results, commenting that:

Zimbabwe is the second-most failed state, just ahead of Sudan, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Yet Zimbabwe has no discernible civil warfare. Its government does prey harshly on any opposition, but the Zimbabwean state has not lost its monopoly control of violence and should therefore not be considered failed. And though there are simmering pockets of conflict in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, these states have failed only if their provision of political goods to the entire population has conclusively fallen to the lowest ranking among regional peers…

…Finer and more accurate distinctions among states are always preferable, especially with the world’s least effective–and most complicated–countries. A more objective system of rankings would better help policymakers analyze the options available and choose the prescriptions that best fit the country in peril.

Indeed, the Index’s rankings grow murkier towards the middle of the list, especially with states “in danger” of failure. It is difficult to objectively say, for instance, that China, despite enormous wealth disparities and violent ethnic tensions with its Muslim Uighur population, is more of a failed state than Algeria, a country still grappling with the legacy of its vicious civil war and with significantly lower prospects for economic growth.

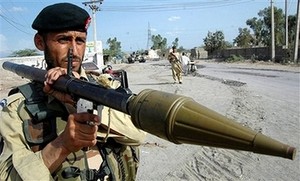

It is equally difficult to say that Pakistan deserves its spot at number ten on the list, only three spots behind its neighbor Afghanistan, and somehow two spots ahead of Haiti. Undoubtedly, Pakistan’s low ranking comes in large part from the violent Taliban insurgency that has reached uncomfortably close to the capital of Islamabad, and has engulfed the major city of Peshawar.

Moreover, the recent combat operations in the Swat Valley created over two million refugees, one of the categories that the Index tracks. And the prospect of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons falling into the hands of terrorists who hold sway in much of Pakistan’s troubled tribal areas is, needless to say, terrifying.

But as Peter Bergen, the Co-Director of the New America Foundation’s Counterterrorism Strategy Initiative, pointed out in April, it is a mistake to say that Pakistan is failing. As Bergen notes, despite Pakistan’s economic and security problems, it is not on the verge of collapse. Pakistan’s strong civil society, independent judiciary (recall the “lawyer’s movement” largely responsible for the peaceful ouster of Pervez Musharraf), and new-found will to fight the Taliban are all encouraging signs.

Pakistan and many other states are hardly secure, and far from perfect. But it is important to remember that in measuring the stability of countries, statistics only tell part of the story.

— Andrew Lebovich

10 comments on “Measuring Failure”