The slew of stories on the fallout from rising food prices have primarily concentrated on the immediate political effects of riots and social upheaval mostly in developing nations. But the long term political effects — especially if high prices endure as some reporting and expertise suggests — could follow the “energy security” trend and pose real implications for balance-of-power politics.

The lesser reported story is that the spike in food prices has precipitated interesting deals and swaps between nations — not simply in exchange for food stuffs but for more strategic assets and commodities (e.g. land and gas). Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal page one coverage of the food crisis seemed to hint at this emerging effect producing some odd-couple partnerships:

With the international financial institutions working on a slow track, countries have been cutting their own deals. Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko said on Tuesday that he had agreed to let Libya grow wheat on 247,000 acres of land in the Ukraine. In exchange, Libya promised to include the former Soviet republic in construction and gas deals.

Brazil recently invited Egypt’s minister of commerce to discuss a possible trade deal which would have a strong agriculture component. China also cut its first free-trade deal with a rich country, picking New Zealand, a major food exporter, and is talking about a pact with Australia, another big agricultural producer.

Meanwhile, Uganda plans to sell more coffee, milk and bananas to India. “Our problem is too much food and little market,” Uganda President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni told reporters, according to news reports.

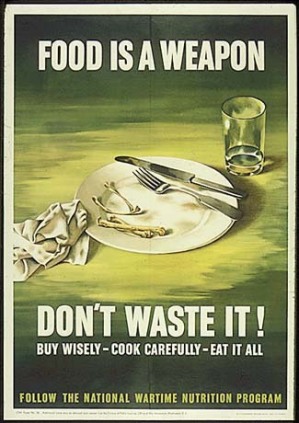

This trend makes make one curious whether food will also follow the path of energy products — like the rise of the national oil company — steered by national interests towards less open markets to be wielded as the next geopolitical asset or weapon.

If OPEC is globally recognized as a cartel that has produced inordinate gains and influence for otherwise less than ordinary nation states, it should come as no surprise that leaders seeking to maximize national self-interest and unhindered by moral scruples will soon use food to that same end.

These vulnerabilities could even be magnified if this food crisis turns out to be a result of something more structural in nature than the global food stock — namely the global food supply chain.

— Sameer Lalwani

8 comments on “Food as a (re)New(ed) Strategic Lever”