This is a guest note by Sarah Stephens, Director of the Center for Democracy in the Americas

This is a guest note by Sarah Stephens, Director of the Center for Democracy in the Americas

On October 28th, the United Nations General Assembly is expected to vote on a resolution condemning the United States embargo against Cuba.

If past is prologue, it will pass resoundingly. The General Assembly has adopted similar measures in each of the last seventeen years; in 2008, by a margin of 185-3. But that was a condemnation of an embargo enforced, energetically and unapologetically, by the administration of George W. Bush. The vote this year takes place for the first time on President Obama’s watch, and so has special significance.

The Secretary-General has prepared a public report that catalogues what UN members and UN organizations say about the embargo.

This document is a powerful reminder that the U.S. embargo is viewed internationally with great seriousness and in ways that are deeply damaging to U.S. interests and our image overseas.

Lest anyone think this policy is only provocative to nations in the non-aligned world, its opponents include Australia, Brazil, China, Colombia, Egypt, the European Union, India, Japan, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Russia.

They are plain-spoken in their opposition. Australia reminds us it votes “consistently” against the embargo. Brazil says it is the “Cuban people who suffer the most from the blockade.” China says the embargo “serves no purpose other than to keep tensions high between two neighboring countries and inflict tremendous hardship and suffering on the people of Cuba, especially women and children.” Egypt and India condemn the extra-territorial reach of our sanctions, which Japan says run “counter to the provisions of international law.” Mexico calls these measures coercive. Russia “rejects” the embargo. Nations across the planet have enacted laws making it illegal for their companies to comply.

Our policy is especially controversial in our own hemisphere, where the U.S. alone is without diplomatic relations with Cuba, and where forum after forum — including the Rio Group, the Ibero-American Summit, the Heads of State of Latin America and the Caribbean, and CARICOM — has rejected the embargo and called for its repeal.

Beyond our diplomatic interests, the report forces us to move beyond the stale, political debate in which the embargo is most often framed (where every problem on the island is blamed on either Cuba’s system or U.S. policy) and to confront the significant injuries this policy inflicts on ordinary Cubans.

It reminds us:

• The embargo stops Cuba from obtaining diagnostic equipment or replacement parts for equipment used in the detection of breast, colon, and prostate cancer.

• The embargo stops Cuba from obtaining patented materials that are needed for pediatric cardiac surgery and the diagnosis of pediatric illnesses.

• The embargo prevents Cuba from purchasing antiretroviral drugs for the treatment of HIV-AIDS from U.S. sources of the medication.

• The embargo stops Cuba from obtaining needed supplies for the diagnosis of Downs’ Syndrome.

• Under the embargo, Cuba cannot buy construction materials from the nearby U.S. market to assist in its hurricane recovery.

• While food sales are legal, regulatory impediments drive up the costs of commodities that Cuba wants to buy from U.S. suppliers, and forces them in many cases to turn to other more expensive and distant sources of nutrition for their people.

• Because our market is closed to their goods, Cuba cannot sell products like coffee, honey, tobacco, live lobsters and other items that would provide jobs and opportunities for average Cubans.

This list, abbreviated for space, is actually much longer, more vivid and troubling, as the report documents case after case of how our embargo affects daily life in Cuba. And for what reason? Because it will someday force the Cuban government to dismantle its system? As a bargaining chip? These arguments have proven false and futile over the decades and what the UN has been trying to tell us since 1992 is that they should be abandoned along with a policy that has so outlived its usefulness.

And yet, it is now the Obama administration supporting and enforcing the embargo — still following Bush-era rules that thwart U.S. agriculture sales; still levying stiff penalties for violations of the regulations; still stopping prominent Cubans from visiting the United States; still refusing to use its executive authority to allow American artists, the faith community, academics, and other proponents of engagement and exchange to visit Cuba as representatives of our country and its ideals.

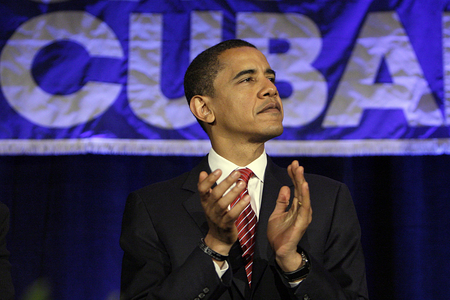

To his credit, President Obama has taken some useful steps to change U.S. policy toward Cuba. He repealed the cruel Bush administration rules on family travel that divided Cuban families. He joined efforts by the OAS to lift Cuba’s suspension from that organization. He has opened a direct channel of negotiations with Cuba’s government on matters that include migration, resuming direct mail service, and relaxing the restrictions that Cuban and U.S. diplomats face in doing their jobs in each of our nation’s capitals.

This is a start, but more — much more — needs to be done. Not because the UN says so, but because our country needs to embrace the world not as we found it in 1959 — or in 2008 — but as it exists today.

President Obama can do this. Our times demand that he do so.

— Sarah Stephens

5 comments on “U.N. Vote to Condemn (Obama’s?) Embargo on Cuba”