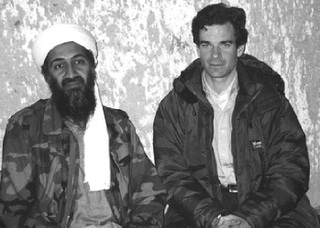

I just read a passage written by Peter Bergen, my colleague at the New America Foundation and a contributor to Anderson Cooper’s AC360.

Bergen, who has been the lead chronicler of the iconic Islamic terrorist now joined by my other colleague Steve Coll who recently authored The Bin Ladens, says little new in his commentary on the “long, fruitless hunt for Bin Laden” that he hasn’t said before.

He does reflect on the seeming disregard bin Laden has for either his much discussed health problems or America’s dogged hunt for him.

What is so strange to me is that Bergen has to keep saying what he has been saying over and over and over again. Bergen’s piece, in my view, includes a thread by which to find bin Laden.

He writes:

Seven years after 9/11 the author of the largest mass murder in American history is free, almost certainly living in Pakistan, which is, at least nominally, a close ally in the US-led ‘war on terror’. As he no doubt savors the anniversary of his greatest “triumph” Osama bin Laden seems untroubled by serious kidney illness as was once rumored, nor does he appear to be troubled by American efforts to find him.

Since his disappearance at the battle of Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan in mid- December 2001 US intelligence agencies have not had any definitive information about the al Qaeda’s leader’s whereabouts. While there are informed hypotheses that he is in the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan, on the Afghan border, perhaps in one of the more northerly areas such as Bajaur, these are simply hypotheses not actionable intelligence. In other words, American intelligence agencies have nothing of any substance on bin Laden. Given the hundreds of billions of dollars that the ‘war on terror’ has consumed the failure to capture or kill al Qaeda’s leader has been one of its signal failures.

That said, it is worth bearing in mind that finding any one individual can be hard. Think of Mohamed Aideed, the anti-American Somali warlord who was known to be in Mogadishu, the capital city of Somalia in 1993, yet some 20,000 US soldiers deployed there were not able to find him. Think also of Radovan Karadzic, the alleged Bosnian Serb war criminal arrested in July in Belgrade who it took more than a decade to track down after the end of the civil war in the former Yugoslavia, and he was hiding in a relatively small country in Europe, not the badlands of the Afghan-Pakistan border.

And given the fact that bin Laden is not making obvious errors such as talking on phones the signals of which can be intercepted and the fact that no one in his immediate circle will rat him out for the long-advertised cash rewards for his head it is likely that al Qaeda’s leader could evade detection for years or even decades.

There are, however, areas where al Qaeda’s leader is vulnerable. The most obvious being his continuing penchant for releasing audio- and videotapes. He has released around twenty since 9 /11. Those tapes give strategic guidance to al Qaeda and the wider militant jihadist movement, but they also provide a window of opportunity to find bin Laden as the chain of custody of those tapes eventually leads back to him.

Let me restate that last bit.

Osama bin Laden’s chief vulnerability is “his continuing penchant for releasing audio- and videotapes.”

Bergen is right — and to the best of my knowledge, all has not been done to capitalize on the natural vulnerabilities of the media wing of the bin Laden/al Qaeda operation. I’m sure we are trailing al Jazeera types in foreign countries, monitoring their phones, and trying to piece together how bin Laden so regularly ascertains video production capabilities and tapes and distributes these to Arab media. But clearly, we have not been able to apply the intelligence resources needed to penetrate this complex challenge. And we should have been able to years ago with painstaking observation, coding of purchased tapes in the Arab region, and other strategies that might have yielded better results than we have achieved thus far.

Early in the post-9/11 bin Laden chase, I thought he might be possibly lured out by a Unabomber-like appeal to the Saudi terrorist’s vanity and the opportunity for him to talk about his objectives.

I believed that an organization — perhaps a think tank — in Washington could generate a platform — and invite the likes of Vice President Richard Cheney, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz or Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, former President Bill Clinton, perhaps Colin Powell or other luminaries like Jimmy Carter, James Baker, and the like into a top tier discussion about America’s role and place in the world. Behind a cloak might be a large screen labeled “Special Guest.”

You probably know who that “special guest” could have been.

The think tank or NGO could have tried to work through the various Western and non-Western journalists who had had contact with al Qaeda to offer bin Laden an opportunity to appear “virtually” on stage with the key leadership of a nation he had decided to attack. In this theoretical scenario, the organizer would have told his contacts that they could do all they could do to anonymize and hide bin Laden’s digital whereabouts — and that the organization would not announce his identity until bin Laden was ready to speak.

Both to prevent the organizer from being charged with some crime and because the mission of capturing and/or killing bin Laden was legitimate, the organizer/think tank would have given national intelligence authorities everything they had in the hopes that the nation’s defense/intelligence capacity could overwhelm any of the measures al Qaeda was taking to anonymize and hide his live performance.

This never happened — but I thought a long time about it. I thought it could work.

Much later, I thought that this scenario — which may sound silly or naive to some — nonetheless would be great in a high-action sitcom drama or in an intel thriller on the Middle East. But I’m realizing that David Ignatius is filling that role for the moment.

I agree with Peter Bergen that bin Laden himself both matters and doesn’t matter. He matters because he has become an iconic figure whose myth grows, like Jesse James’ reputation did, the longer he defies the market expectations that he will one day be caught and shut down.

He doesn’t matter on another front as his operation, both the direct al Qaeda groups who seem loyal to and depend on him for inspiration and perhaps support and those that self-organize in the Middle East and around the world seem to not need him and his organizational genius to pursue their objectives and generate damage.

Again, my scenario never happened — but Peter Bergen’s notion of exploiting the vulnerabilities of a complex media operation probably require fewer innocents-killing bombing campaigns and more hard thinking, laying of traps, and ingenuity.

— Steve Clemons

15 comments on “Why Are We Not Appealing to the Vanity of Bin Laden and Al Zawahiri?”