This is the second installment in James P. Pinkerton‘s provocative health care policy series for The Washington Note.

Pinkerton is a contributor to the Fox News Channel and a policy blogger. Pinkerton is also fellow at the New America Foundation, and contributing editor at The American Conservative magazine.

“Playing God.” We all know the phrase, because we all know the temptation. That is, we know the temptation to make decisions for others – even the most profound decisions of life and death.

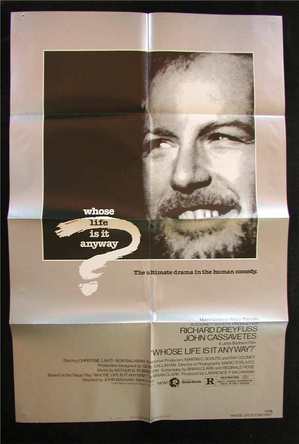

Remember the play/movie “Whose Life Is It Anyway?” It was a poignant tale of a man, paralyzed from the neck down in an accident, who wants to end his life. Such “death with dignity”-type assisted-suicide cases are controversial and the stuff of great drama, because those with power are able to determine the life, or death, of those without power.

But an even larger issue is the great drama of medicine – who is healed and who is not, who lives and who dies. The elites prefer the dry phrase “health care” over the evocative word “medicine”; it is their way of lulling us to sleep while they make decisions for us. So the elites prefer that we not discuss Serious Medicine, and whether or not we all get it, because any such discussion would get in the way of elite planning.

And the elites, of course, are all planning to spend less on medicine. They know that for every individual like the character who wants to die (played by Richard Dreyfuss in the 1981 film), there are 100, or a 1000, who want to live – and that costs money.

So the question for today: Do the Powers That Be think that we are worth saving, or do they think that it’s cheaper to get rid of us? The answer would seem to be the latter. That’s the consensus emerging from the self-appointed and self-reinforcing circle of “experts” who have occupied the commanding heights of “health care policy” and related fields of arcana, such as “bioethics.” The mantra of The Experts is simple and oft-repeated: Cut back on care, do less, save money – in keeping with an overall Green-inflected sense of the limits to growth, of the limits on human potential.

And so we have “a duty to die and get out of the way,” as former Colorado governor Richard Lamm revealingly asserted back in 1984. Few have been so candid since, but one maven of that school, Peter Orszag – a leading Democratic voice on health and fiscal policy for years, now director of the Obama administration’s Office of Management and Budget – has long argued for the rationing and restriction of health care. Here’s one snippet of his argument, as noted by Peter Ferrara in the pages of National Review:

Future increases in spending could be moderated if costly new medical services were adopted more selectively in the future than they have been in the past, and if the diffusion of existing costly services was slowed.

Now that puts the hay down where the horse can get it. New medical services should be “adopted more selectively,” and “the diffusion of existing costly services [should be] slowed.” Got that? In other words, ordinary people would lose out on medical care – and deliberately so. One can only ask: Shouldn’t these policy-choices be discussed more openly? Shouldn’t the citizens and health-stakeholders of this country get more of a say – instead of being spin-doctored into scarcity masquerading as “universality”?

Today’s elites don’t think that decision-making should be shared. Of course, elites never want to share power. That’s why they’re elites.

Yet surely the rich have nothing to fear from Obamacare, they might be telling themselves. And in the short run, there’s no need for, say, Steve Jobs to worry, because as he demonstrated earlier this year, he has a blank check for his own health care.

But in the long run, Jobs and everyone else, no matter how rich, should be worrying – because the trajectory of future health-care research is being flattened. Of course, the Orszagian health-care rationers will deny they are cutting back on research and, subsequently, development. We are just controlling costs, they say.

But history shows that R&D comes from within big surpluses, from surpluses that allow scientists and engineers to noodle around on blue-sky projects. That was the story, for example, of Bell Labs, established by AT&T in 1925. “Ma Bell” was reaping monopoly profits in those days, and so it could afford to let Bell Labs employees delve into abstruse projects, many of which had little to do with the humble telephone.

The non-bottom line byproduct of this flush funding was six Nobel Prizes – including the 1997 Nobel Prize for Physics won by Steven Chu, now Secretary of Energy. But until the megacompany was broken up by anti-trusters in 1984, AT&T obviously thought it benefited from its expenditures on Bell Labs; its scientists developed everything from the transistor to the laser, from UNIX to radio astronomy. The generous benefit to all humanity from this nominally for-profit enterprise has been incalculable.

By contrast, the phone companies today are lean-and-mean profit machines; they are mostly marketing operations, and so the forward progress in telecommunications is now coming from elsewhere, from the super-profits generated by companies such as Apple and Google, which carry on the Bell Labs tradition.

The point is this: Be it electronics or health care, the money needed to fund R&D – and then to build the momentum needed for mass production – can come only from an initial surplus. And such mass production, of course, eventually leads to a dramatic lowering of costs. That’s the rule of technological development: New things are expensive, until they get cheap. No way around it. And so if we are cheap in the beginning, as a matter of policy, not only will we neglect discovery and innovation, but we will never get to the point where we can bring down the per-unit cost. In being cheap, we will simply have less.

So let’s take an illustrative example from recent medical history: AIDS. Is AIDS medicine expensive? Sure it is. But how much was AIDS costing us when it was cutting people down in the prime of their lives? How much output and creativity was lost when Halston died? Or Keith Haring? Or Steve Rubell? Or Stewart McKinney? Or Ryan White, the unlucky recipient of a tainted blood transfusion who died in 1990 at the age of 18: Who knows what he would have done with his life?

Those losses were bad enough. Fortunately, nobody in authority said that AIDS victims had “a duty to die and get out of the way.” Instead, as a civilization we faced up to the challenge and spent what it took to address the epidemic. Medical research complexes, such as NIH, functioned the way Bell Labs once functioned; they threw money at smart people, confident that the human brain would eventually solve the riddle of HIV. Out of that riddle-solving came new treatments, such as AZT, which cost billions to develop, but which can now be retailed relatively cheaply. And so today, in the West at least, AIDS is a chronic problem, but not a mass-killer.

And so anyone who cares about Serious Medicine – which is to say, anyone who cares about the actual stuff of medicine, and about actually helping people, as opposed to the abstractions of “health care policy” – should be alarmed by the downward spiral of the debate in Washington DC these days. Orzsag & Co. are working to “control costs,” even in advance of cost-control legislation. Their latest tactic has been to jawbone Big Medicine into “voluntary” price reductions so that the Obama administration can declare victory on cost control.

But ask yourself: Isn’t it obvious that if medical players know they will be getting less, they will then be doing less? Shouldn’t we be figuring out how to incentivize, mandate, or otherwise encourage medical science to do more, not less?

Thus allegations made by Kimberly Strassel in her Wall Street Journal column on Friday command our attention. Strassel asserts that health care lobbyists are more loyal to cost-controllers in Washington than they are to their own outside-the-Beltway employers – who, being capitalists, obviously want bigger and better. But inside the Beltway, health care has been waylaid by Club of Rome-type growth-limiters, as well as fiscal bean-counters, focused on the shortest of medical short terms. As Strassel puts it:

Health-care lobbying has been turned on its head: The new cabal of Democratic lobbyists does not exist to protect the industry from Congress. It exists to present Democratic ultimatums to business.

If Strassel is correct – and I don’t doubt that there are differing opinions and conclusions, and we should all hear them – then the true long-term interests of Americans are being mocked. Our future well-being is being cynically sacrificed on the altar of phony claims about the next few fiscal years.

Because make no mistake: If we spend less now on health care, we will get less health in the future. More people will die or be disabled before their time, and that will be costly, indeed.

But those who want “play God” will be satisfied, because they will have had the pleasure of toying and tinkering with the rest of us.

— James Pinkerton

20 comments on “A Provocation From James Pinkerton: Playing God — Whose Lives Are These Anyway?”